When ancient feng shui meets modern biophilic science

By Joseph Wong

In the pursuit of the perfect home, the conversation has long been split between two worlds: the intuitive, energy-driven wisdom of the East and the empirical, data-backed science of the West. On one side, we have feng shui, the thousand-year-old practice of harmonising Qi (energy). On the other hand, we have biophilic design, the 21st-century architectural movement rooted in our biological need to connect with nature.

Today, these two disciplines are converging. Designers and home owners are discovering that they are two sides of the same coin, aiming to reduce stress, boost productivity and create vibrant environments by bringing the outdoors in.

At its core, biophilic design is the science-backed modernisation of what feng shui masters have sensed for centuries. While a feng shui practitioner might suggest a specific layout to improve wealth flow, a biophilic architect would argue that the same layout provides prospect and refuge—a psychological state of safety that lowers cortisol levels.

“From an architectural perspective, many biophilic layouts supported by environmental psychology closely align with traditional feng shui principles. Research published in sources such as the Journal of Biophilic Design consistently identifies key design attributes, including visual connections to nature, dynamic natural light, water, airflow and the principles of prospect and refuge, as elements that measurably enhance cognitive, emotional and physiological well-being. These evidence-based outcomes closely parallel feng shui concepts of auspicious positioning, spatial balance and unobstructed energy flow,” said ADJ Architecture principal partner Alvin Lim.

For example, Lim pointed out that office layouts that position workstations to face entrances, rather than placing occupants with their backs to doors, have been shown to improve perceived control and reduce stress. Similarly, locating communal spaces near natural light or gardens increases social interaction and overall well-being.

“While feng shui frames these effects in terms of managing Qi, modern architecture evaluates them through indicators such as cognitive performance, productivity and stress levels. In many ways, both traditions describe the same human responses, expressed through different conceptual languages.

“Locally, offices and residences that orient key spaces toward greenery, such as internal courtyards, pocket parks or city views, consistently report higher levels of user satisfaction. More developments are adopting this approach by incorporating landscape buffers and maximising daylight penetration to enhance comfort. While architects may justify these strategies through environmental psychology and sustainability metrics, they closely reflect long-standing feng shui ideas of balance, openness and harmony,” noted Lim, who is also a council member of the Malaysian Institute of Architects (PAM).

Command position vs prospect and refuge

One of the most striking overlaps is the concept of security. In feng shui, the command position dictates that a person’s bed or desk should have a clear view of the door without being directly in line with it. This mirrors the biophilic principle of prospect and refuge.

Five Elements Mastery founder Professor Joe Choo explains that this alignment is deeply rooted in human evolution.

“The command position places key furniture such as beds, working desks and seating where one has a clear view of the entrance without being directly in line with it, creating a sense of control, awareness and security,” she says. “From a psychological and physiological perspective, humans naturally feel calmer and more confident when they can observe their surroundings while remaining safely sheltered. In feng shui practice, this balance reduces subconscious stress and allows energy to settle smoothly, rather than remaining defensive or chaotic”.

However, Environology Malaysia’s honorary secretary Stephen Chin offers a more pragmatic, classical perspective. While acknowledging the underlying human experience, he points to the Eight Mansions (Ba Zhai) system.

Security and refuge arise naturally when a property conforms to landform energy and the individual operates from sectors that support them, he explained. “When someone occupies a space that matches their favourable sectors—for example, by having a main entrance or placing a bed or work chair there—the energy naturally supports clearer thinking, steadier emotions, better health and sound judgement. This, in turn, leads to better decision-making, improved opportunities and a greater sense of safety and confidence,” he added.

The vitality of natural elements

Both philosophies view the home as a living organism but they define elements differently. In biophilia, plants are air purifiers; in feng shui, they represent the wood element.

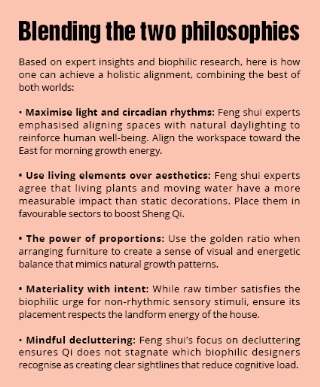

Choo, who is a feng shui master, speaker, author, consultant and trainer, noted that the rise of sustainable architecture has naturally echoed feng shui principles. She pointed to the golden rule found in nature. Applying these proportions to furniture layout and circulation paths helps create environments where energy flows organically, she said. For Choo, living plants and water features are essential because they generate Sheng Qi (living energy).

Chin, however, cautioned against taking the five elements too literally. “The five elements—wood, fire, earth, metal and water—are symbolic descriptions of energy states and transformation cycles, not physical substances,” he asserted. While sustainable materials like timber or stone support biophilic goals, Chin argued they do not automatically fulfil a feng shui elemental requirement unless placed correctly according to a person’s personal source code.

Balancing the equation

Modern homes are increasingly dominated by smart technology which both experts categorise as highly Yang (active/stimulating) energy. The challenge for 2026 is keeping these spaces grounded.

Choo suggested that while technology improves efficiency, an excess of technological Yang leads to mental fatigue. “To keep the home’s energy grounded and balanced, I often recommend biophilic and natural adjustments that soften and anchor this intensity. Elements such as natural materials, warm textures, earth-toned colours, gentle lighting and visual connections to greenery help introduce a calming, yin quality that stabilises the overall energy,” she said.

Chin takes a more empirical approach to technology. “We are already surrounded by radio frequencies from all directions. Most of us also carry a radio transmitter and computer in our pockets—the smartphone. If technology affects a space, we don’t guess or symbolise. We measure. Adjustments are made based on readings from the luopan (geomancy compass). If radiation intensity is genuinely a concern, the only meaningful solutions are physical: shielding, iron cladding, fencing or in extreme cases, a Faraday-type enclosure,” said Chin.

On a more scientific level, Lim said studies by the International Biophilic Products Association show that biophilic workplace features can increase creativity and productivity by double-digit percentages.

“Although users may not consciously articulate a need for stronger connections to nature, architectural research reveals a deep and often subconscious human preference for environments that feel uplifting and restorative. As a result, workspace quality is increasingly defined not only by technology or luxury but also by natural connectivity that supports comfort, health and overall satisfaction. Architecture that reconnects people with nature creates workplaces that people genuinely want to return to,” he said.

Activating the wealth corner without light

A common modern dilemma is the windowless wealth corner. Traditional biophilia struggles with dark spaces but feng shui offers solutions.

Choo recommended activating these areas with genuine living elements. She said genuine crystals help stabilise energy while low-light plants introduce vitality. A small, well-maintained water feature can keep energy moving and prevent stagnation even without natural light.

Chin, however, dispelled the myth of the wealth corner as a magical shrine. It simply means that operating from that favourable sector enhances an individual’s capacity to make sound financial decisions, he said. He adds a critical warning for shared spaces: “If you share the space, your plants, crystals or features may support you while negatively affecting someone else. This is why I am very cautious about giving general tips.”

Lim noted that while feng shui often approaches orientation symbolically, viewing it as a way to invite good fortune and harmonious energy, contemporary sustainability and health-driven design applies orientation scientifically to optimise light quality and occupant well-being. Both traditions emphasise the importance of orientation; one articulates its value through traditional wisdom while the other substantiates it with measurable physiological benefits.

“Today, architects rely on environmental simulations and performance data to validate these decisions, yet the underlying spatial logic remains consistent,” he added.

A new design standard

As we look toward 2026, we are moving away from seeing homes as mere shelters and toward seeing them as wellness engines. The convergence of Choo’s focus on natural proportions, Chin’s emphasis on landform pragmatism and Lim’s performance-based approach shows that while the language may differ, the goal is identical: a space that supports human flourishing.

By modernising ancient wisdom through contemporary research, the blend of feng shui and biophilic design offers a blueprint for the modern sanctuary. It is no longer about choosing between superstition and science; it is about designing a life that is, quite literally, in tune with nature.

Stay ahead of the crowd and enjoy fresh insights on real estate, property development and lifestyle trends when you subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media